How to Identify Knotweed

Written by Maria Goncharova, edited by Hannah Munnalall

Knotweed species are native to East Asia and have become of particular concern as three representatives of the complex, specifically Japanese, Giant, and Bohemian knotweed, are considered invasive species and pose significant socioeconomical and ecological damage5. Out of these, Bohemian knotweed is the most prevalent in North America1.

In order to manage and control knotweed, it is important to first locate and identify knotweed in the area. Identifying the specific species of knotweed is not recommended, as there are large variations in their physical properties. Additionally, as Bohemian Knotweed is a hybrid of both Giant and Japanese knotweed, it has physical properties of both of its parents and is frequently misidentified as one of the parents3.

Therefore, this guide is to help identify knotweed in general, and not to identify particular knotweed species.

Stems

Knotweed species have a hollow stem, similar to bamboo2. Additionally, while Japanese knotweed only grows up to 1-2 meters, Giant and Bohemian knotweed can grow as tall as 5 meters5

Leaves

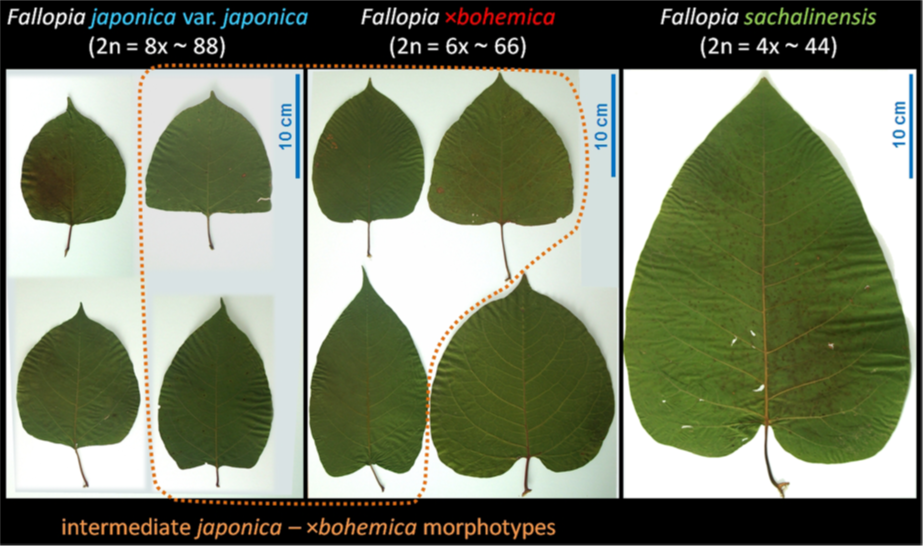

Knotweed leaves grow out of the stems in a zig zag like fashion, but leaf shape slightly differs depending on the specific species. For example, Giant knotweed usually has heart shaped leaves while Japanese knotweed leaves are straight edged at the base. Bohemian knotweed, true to the nature of a hybrid, has a mix of both of its parents’ leaves4.

However, these are general features; the plants still exhibit variation in leaf shape. This means that leaf shape is not an accurate identification feature of the specific knotweed species. The leaf length can range from 8-30 cm, with Japanese knotweed usually having smaller leaves and Giant knotweed exhibiting the biggest leaves4.

Seasonal variation

In late summer/early fall, knotweed starts to flower and by mid to late fall, seeds develop. As knotweed is a deciduous shrub, it sheds its leaves later in the fall, around the time when seeds mature1.

After shedding, during wintertime, knotweed stems get killed by the frost and break off, forming a dense litter layer7. Finally in the spring, new knotweed shoots come out of the ground, continuing the cycle.

References

1Claeson SM, LeRoy CJ, Barry JR, Kuehn KA (2013) Impacts of invasive riparian knotweed on litter decomposition, aquatic fungi, and macroinvertebrates. Biological Invasions, 16(7), 1531–1544 doi:10.1007/s10530-013-0589-6

2Martin FM (2019) The study of the spatial dynamics of Asian knotweeds (Reynoutria spp.) across scales and its contribution for management improvement (Doctoral thesis, Universite Grenoble Alpes). Available from HAL Archives.

3Zika P, Jacobson A (2003). An overlooked hybrid Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum x sachalinense; polygonaceae) in North America. Rhodora 105 (922) 143-152

4Barney JN, Tharayil N, DiTommaso A, Bhowmik PC (2006). The biology of Invasive alien plants in Canada. Polygonum cuspodatum Sieb. & Zucc. [Fallopia japonica (Houtt.) Ronse Decr.]. Can. J. Plant Sci. 86: 887-905.

5Mereda P, Kolarikova Z, Hodalova I (2018) Cytological and morphological variation of Fallopia sect. Reynoutria taxa (Polygonaceae) in the Krivanska Mala Fatra Mountains (Slovakia). Biologia. doi:10.2478/s11756-018-00168-w

6Beerling DJ., Bailey JP, Conolly AP (1994) Fallopia japonica (Houtt.) Ronse Decraene. Journal of Ecology 82: 959-979

7Maerz JC, Blossey B, Nuzzo V (2005) Green Frogs Show Reduced Foraging Success in Habitats Invaded by Japanese knotweed. Biodiversity and Conservation 14(12) 2901–2911 doi:10.1007/s10531-004-0223-0